⁐ Index

🞿 About

⁋ Publications

⚷ Public PGP Key

Published June 8th, 2025 from Vancouver, Canada

ஃ is a letter in the Tamil language, pronounced roughly like 'uck'. Every schoolchild and foreign learner is taught this character, usually just after the twelve vowels. But ஃ is not a vowel. Nor is it a consonant. Nor is it actually used in spelling any words in modern Tamil.

ஃ originally represented a breathy 'h' sound used in Old Tamil and its other archaic Dravidian sister-languages. This sound no longer exists in modern Dravidian languages, but the ஃ was recycled as a grammatical marker. Today, it is used to represent sounds from foreign languages that Tamil doesn't have, like an English 'f' (ஃப) or the breathy 'kh' in Genghis Khan, which would be written கெங்கிஸ் ஃகான், reading like: 'kengkis ஃkaan'.

I find this incredibly charming. It's a clever way to make use of an otherwise vestigial linguistic feature, and is an example of a romantic attitude towards language that we do not often see in English.

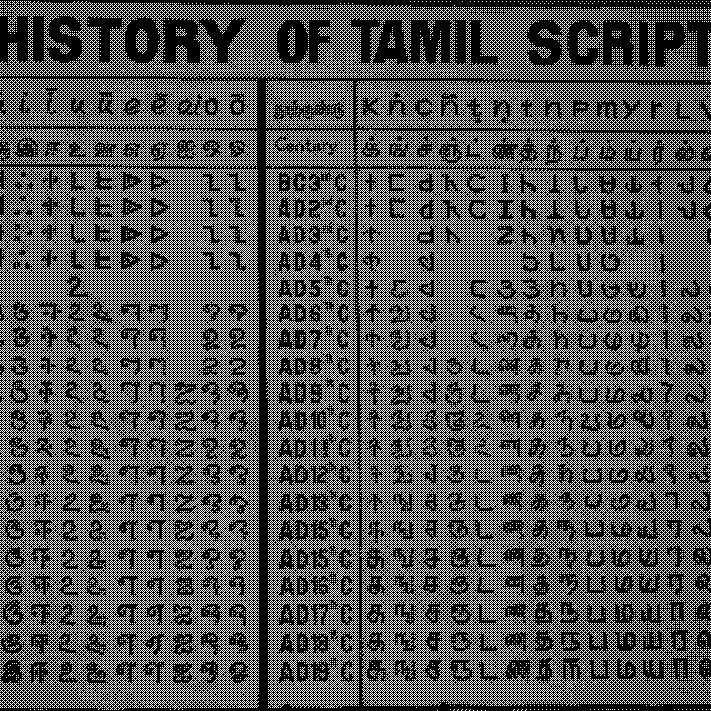

This enduring attachment to a beautiful old symbol like ஃ is symptomatic of the linguistic conservatism and pride which has preserved Tamil as the world's only classical language still in use. Tamil today is written and understood largely the same as it was several thousand years ago when canonical texts like the Thirukkural were being composed. No such relationship survives between Biblical and Modern Hebrew, Vedic Sanskrit and Hindi, nor Homeric and contemporary Greek. Contemporary Tamil, on the other hand, is a bit like if Italians still went around using Latin.

So, what if English was a little bit more like Tamil?

The best English parallel for ஃ would be the thorn: þ. The þ was used in Old and Middle English to represent the 'th' sound at the beginning of 'thick', technically called a voiceless dental fricative. Anglo-Saxons had names like Æþelræd (Aethelred), and were ruled over by a noble class called the æþelingas (aethelings). The þ lived alongside other lost letters like the ash (Æ/ae) and the yogh (Ȝ/y). But unlike them, the þ stayed in use well into Middle English, until it began to be slowly displaced by 'th' starting in the 1300s. It truly fell out of use with the advent of printing, when 'y' became a more common replacement (hence 'ye olde').

It didn't have to be this way. Modern Icelandic has preserved the þ, and it is used every day in ordinary words like "þrír" (three). What if we had been a bit more attached to this unique character, a little less willing to lose our language's Germanic origins amidst the French loanwords and Greek prefixes? If we used þ in English as Tamil does the ஃ, we would not only have retained a charming reminder of our language's history, but have gained a handy representation of unusual sounds.

English speakers are constantly making fools of themselves. A street in Germany goes from being a sharp, peaking 'straSSe' to a 'strass'. I always figured the Greek sandwich was pronounced a 'jyro' until I was corrected at a restaurant in Montreal. Apparently easy anglicisations become landmines dotting our menus and name registries.

If only we were more like Tamil, and employed some signpost like ஃ, a character that could warn us when we were liable to miss something. þ could be that signpost. The often-mispronounced name of Albanian communist dictator Enver Hoxha (not 'hocks-ha', 'hodger') could instead be rendered as Enver Hoþxha. Perhaps my reputation as a cosmopolitan would still be recoverable had the cafe menu only read "þgyro".

The þ is by far the best candidate for this simply because it is more distinct than any other archaic English character: the Æ just looks like an ae, and Ȝ resembles the number three. þ, on the other hand, is so unique that few modern English speakers have any existing pronunciation associated with it. This is helpful, since, just like the contemporary Tamil use of ஃ, this þ would not actually provide any real instructions on the foreign pronounciations any more than ஃகான் directs you to a form a breathy 'KHan' instead of 'uck-kaan'. But it would offer a suggestion, and would be a more humble admission of the English language's limitations than arrogantly attempting to represent all the phonemes of the world in our twenty-six characters.